Accessory Dwellings

A one-stop source about accessory dwelling units, multigenerational homes, laneway houses, ADUs, granny flats, in-law units…

Perspective: How to make accessory dwelling units affordable

I’ve been involved in real estate development and finance for “big” projects for more than 30 years. I was Chief Operating Officer of 42nd Street Redevelopment Corp., which led the $3 Billion redevelopment of Times Square in New York City. I was a member of a team that underwrote $400 million in construction loans, of which the largest was for the construction of the first phase of Newport City, in Jersey City NJ. And I’ve done more conventional shopping center and townhouse projects.

But this experience leads me to believe the key to making projects manageable and low-risk is to keep the scale small. That’s one of the many reasons I’ve started a nonprofit, Backyard Housing Group, to advocate for accessory dwelling units (ADUs). Also known as granny flats, casitas, mother-in-law units, and a dozen other names, ADUs may be one of the most workable solutions to our national housing crisis. These small dwellings, built within or on the grounds of a traditional single family home, promise numerous benefits for the homeowner and community.

But realizing those benefits won’t be easy, and that’s where commercial real estate may provide some perspective.

THE PROMISE

ADUs are unusual in that they are most often created by homeowners rather than professional developers. Among the more commonly promoted benefits for the homeowner are generating needed income through rents, providing multi-generational living flexibility, generating space for live/work arrangements, and providing caregiver housing.

ADUs promise benefits for the community too: affordable housing with no land costs or structured incentives; development that is distributed rather than concentrated (which might minimize environmental and social impacts); heterogeneous rather than homogeneous neighborhoods; and contributions toward economic development — as rental income paid to homeowners should stay local.

While formal research on these claims is taking time to accumulate, the evidence so far, both formal and anecdotal, has encouraged numerous prominent organizations to support ADUs. AARP recently published The ABC’s of ADUs; the Florida Housing Coalition published Accessory Dwelling Units: A Smart Growth Tool for Providing Affordable Housing ; and the American Planning Association has published numerous guides to ADU practice.

Here in my home of Wilmington, North Carolina, the city is warming to the potential of the form.

“Accessory dwelling units were identified by the affordable housing task force for the city and the county as an opportunity to expand our affordable housing stock,” Wilmington Director of Planning Glenn Harbeck told the City Council, as reported by the Port City Daily.

“Before WWII, accessory housing units were as common as an automobile, a bicycle, anything else … they were extremely common items in the United States. It wasn’t until after WWII for some reason we tried to homogenize our residential areas into exclusive single-family residential areas,” Harbeck said.

Thanks to this mindset of development, Harbeck argued, it has become increasingly difficult for anyone to construct ADUs due to zoning regulations. This has to change if the city wants to utilize ADUs, he said.

THE CHALLENGE OF PROJECT FINANCING

But realizing the benefits of ADUs is not as simple as merely changing zoning rules. A survey conducted by the City of Durham found that there is a need to educate the homeowner’s on how to go about building an ADU and obtaining financing for construction. Financing is also emphasized in a study by The Urban Land Institute, University of Texas at Austin, Center for Community Innovation, and Terner Center for Housing Innovation, “Jumpstarting The Market For Accessory Dwelling Units”. To quote the latter:

Many studies have explored financial barriers, including high upfront costs and the inability to access loans. A study of Oregon ADU owners found that most owners actually built theirs out of cash savings… Structural challenges also make borrowing for an ADU difficult. Most lending institutions do not allow income from the ADU to factor into the qualifying income of the homeowner apply for the loan and in many cases the value of the ADU value of the unbuilt ADU to estimate market value of a residential property. Because of this and other factors, homes with ADUs were found in one study to be under-valued by up to 9.8%.

Financing affects the production of “affordable” ADUs in several ways, because there are several sides to the affordable housing discussion when ADUs are considered. One is the tenant’s point of view: is the rent affordable? The second is the homeowner’s point of view: can the income from the ADU help subsidize their cost of living to keep them in their primary residence?

If, as is suggested by the Terner Center report, most ADUs are built using a patchwork of cash, home equity, and family/friend loans, then it seems unlikely that ADUs will be built by the kind of homeowners that most need the extra income. And if a homeowner does manage to jump through the hoops to build an ADU, why would the owner rent the unit out at affordable rates rather than market rates?

A recent study from Edmonton suggests these dynamics are playing out in reality. Edmonton ADUs had average rental prices that were only slightly lower than market rents for comparable dwellings (though there were some interesting instances of individual ADUs priced far below market rates). But, perhaps more discouraging, the developers of ADUs themselves tended to have relatively high incomes — i.e. they were probably not the homeowners most in need of extra income.

Currently there seems to be no form of financing designed with the ADU in mind. Presently in order to obtain funds to construct an ADU, via some combination of home equity and income, homeowners have to be able to document sufficient personal income and current appraised property value, without taking into consideration the future rental income, or future value of the property with a completed ADU. Further impediments to ADU development stem from typical bank requirements that a 1 to 2 year history of rental income is required before a bank will include the ADU rental income as part of the homeowners’ qualification.

These constraints stand in sharp contrast to the way commercial construction loans are structured. Common commercial underwriting standards use income from projected rents upon the completion of the building to calculate the borrower’s qualifying income. Also, commercial lenders include the value of the to-be-built structure when calculating the loan to value ratio. Commercial lenders also include an interest reserve in the development budget, allowing interest to be paid from the construction loan, rather than from the borrower’s pocket.

AN ADU-SPECIFIC FINANCING PROGRAM AND THE COMMUNITY REINVESTMENT ACT (CRA)

I believe a way out of this quandary is the creation of a designated ADU financing program, one that enables, incentivizes and supports home owners in exchange for leasing the ADU at below market rent.

From a finance perspective, a promising source of funds for this “affordable ADU” program would be bank funds required to be invested under the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) is a federal law enacted in 1977 to encourage depository institutions to meet the credit needs of low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. The CRA applies to FDIC-insured depository institutions, including national banks, state-chartered banks, and savings associations.

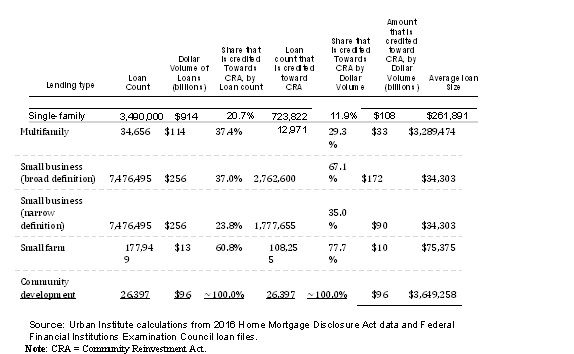

Below is a chart indicating the type of CRA investments being made in the USA. Qualifying CRA investments include; affordable housing (including multifamily rental housing) for low- and moderate-income individuals; community services targeted to low- and moderate-income populations and activities that revitalize or stabilize low- and moderate-income geographies.

The chart shows $108 billion in 2016 went towards single family mortgages, illustrating the size of the pool of funds that could potentially include an ADU lending program.

The form of the financing to homeowners would be a new first mortgage, one that includes both home and ADU structures, at a discounted interest rate invested from each lender’s CRA portfolio. The loan structure would be similar to that offered to commercial developers. This structure would allow projected ADU rents to be included in the applicant’s qualifying income. The value of the future ADU would be included when calculating loan-to-value requirements. An interest reserve would be included as part of the development budget, to pay the interest charges during the construction period.

MANAGING THE PROJECT

But the loan is only part of the program. A holistic ADU program must include project execution support as well, because managing the building project is a significant barrier, according to the Durham survey and the Terner Center report. To quote the latter,

Another barrier can be the experience level of the ADU developer. Those building ADUs tend to be homeowners unfamiliar with real estate and construction and see building an ADU as a major and risky project. Navigating zoning and building codes could be a barrier for those not experienced with development, or concerned about city inspectors flagging unrelated code violations on their lot.

In short, prospective homeowner developers need project management guidance, such as assistance with the permitting process, a review of design alternatives, help with bidding out work and monitoring construction, and finally, once the project is completed, with managing tenant relations.

POSITIVE MOVEMENT

Fortunately some new options have begun to emerge in this space recently. To me, one of the most interesting is the “Backyard Homes Project” from Los Angeles nonprofit LA Más, which offers a bundle of all the resources needed, with financing, design, and construction support in exchange for a pledge to house Section 8 voucher holders in the ADU for at least five years. For their pilot program of 10 units, they received 130 applications.

My own nonprofit, The Backyard Housing Group, is moving towards a 5-unit pilot program in Wilmington NC based on CRA funding. The program will offer the homeowner favorable financing which will not require additional cash to build their Access Dwelling Unit. Instead they will be able to apply to a 1st mortgage covering their house and the cost of their new ADU.

In the budget will be design, permitting, and construction support also landlord training and tenant support services all provided by our nonprofit. In exchange the homeowner will agree for 5 years to rent the unit out at rents that HUD considers as affordable.

The role of the nonprofit in my program is to reduce risks for lenders, homeowners, and renters there by facilitating the building of affordable ADUs. The program helps pre-qualify applicants and their properties to make mortgage origination less cumbersome. Lease-up risks are minimal as “affordable rents” by definition, are below market rents. And the nonprofit’s experience in development and construction helps assure that the project will be realistic and completed.

The appeal of the accessory dwelling unit form is widely recognized. Done right, ADUs can be a win-win situation for the tenant, homeowner and community at large. I hope that ADU development programs like Backyard Housing’s can take the tiny promise represented by an individual ADU project, and spread it to a scale that will move the needle in addressing the national affordable housing crisis.

Great insight and references. Thank you

We have local financing thru Frost Bank, no money down with payment running about $900/month. It has to be your homestead and have 20% equity.

https://www.youtube.com/user/Mikeshelton002

Very good article. I have built two ADU’s in Charlotte, NC and I re-financed each of my properties and used a home equity line of credit to get them both done. Having done this twice, I think the best advice I could give anyone is to find a competent and trustworthy contractor who can finish your project on time and on budget. This can make all the difference between success or failure. I wish I had 10 of these. I could rent them all.

Incisive article with thoughtful ideas. Please keep us informed on the financial front, there is a lot of interest in my area but we need to have properties evaluated using the income versus comp valuation method.

Thank you for for providing this thoughtful and thorough essay. I am going to share it here with my colleagues who are taking a big interest in the subject.

Warm regards,

Rachel Hemmingson

Fully enjoyed reading this article. Plan is to move to Durham, NC and build ADU in son’s backyard, to age in place. Financing options are being explored.