Accessory Dwellings

A one-stop source about accessory dwelling units, multigenerational homes, laneway houses, ADUs, granny flats, in-law units…

Colorado Passed Zoning for ADUs in Urban Areas. What’s Next?

Analysis from a former local elected official and affordable housing champion turned ADU researcher.

By Robin Kniech

(You can jump to the Background on Colorado’s Legislation section below to get right to the new state law and predictions).

Me & ADUs in Denver Leading Up to Colorado’s Legislation

I was called many things during a dozen years on Denver’s City Council. I’ll own the label “houser,” because of my focus on affordability for low-income families. But “ADU advocate” wasn’t one of them.

I’ve known people who lived in ADUs: A young adult in a parent’s property here, a divorcing fellow-elected official there, and now friends managing their own as a rental to help afford their primary home. Yet twenty years ago, as a coalition organizer and equity advocate for a Denver community-based organization seeking to expand access to affordable housing for our lowest income neighbors, I never once thought about an ADU during my work.

In 2011 I was elected to serve as an At-large member of Denver’s City Council. I mostly went about my business as a serious affordable housing champion: creating housing funds, a decade-long journey on inclusionary housing, innovating on homelessness interventions and renter protections. A citywide rezoning in 2010 included standards for ADUs and the city saw a trickle of rezonings and permits in my early years.

I thought about ADUs during Monday night Council meetings. But they lived in the zoning hemisphere of my brain as one-off parcel rezonings. I never opposed them as a form of market-rate housing. I voted for every ADU rezoning I saw. But they didn’t excite me as an affordable housing strategy either.

Until two things changed: First, the pace of ADU rezonings increased, including entire neighborhoods exploring permission to build them. A 2019 comp plan update created clearer support for ADU rezonings citywide. That was followed by reforms to set backs, lot coverage, garage conversion and other barriers that just passed in 2023.

The 2019 Blueprint Denver Plan and its language supporting ADUs.

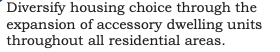

The map below shows the current status of ADU zoning in the city. All but a third of Denver’s residential areas allow them. The process to expand ADUs zoning to those remaining areas, which will ensure Denver conforms with the new state law, began even before its passage.

From Denver Community Planning and Development presentation to Denver City Council, March 18, 2024.

Second, our public Denver Housing Authority took on a pilot to help low- and moderate-income families build affordable ADUs in heavily Latino and lower-income West Denver communities. The neuropathways between the affordable and zoning hemispheres of my brain formed.

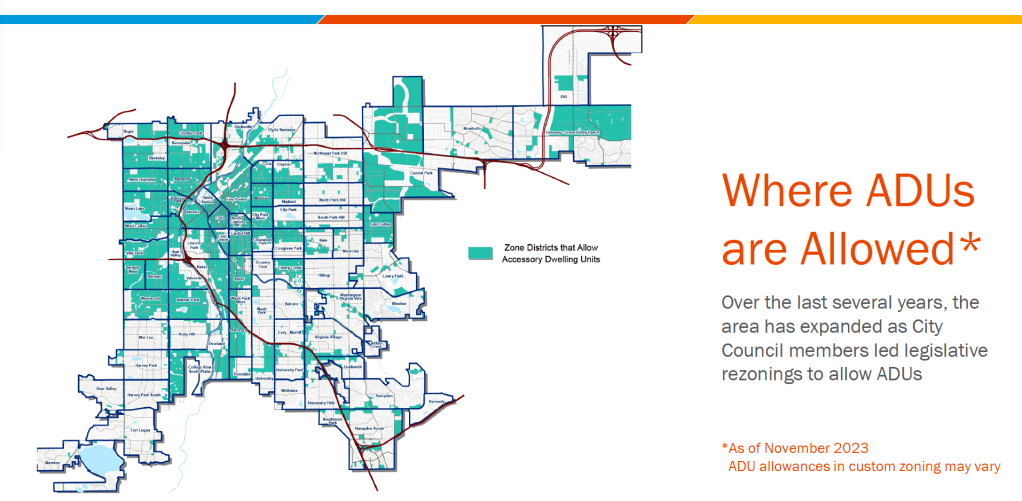

Affordability and equity outcomes from the West Denver Single Family + ADU Pilot Program.

I was all-in for the West Denver Single Family + program (WDSF+), as the pilot came to be known, with its subsidies and rent limits. But with no data at all, at least from our local market, I was skeptical market ADUs would serve households struggling with affordability in my city, one of the most expensive housing markets in the nation when accounting for incomes. In fact, because building ADUs was (and is) expensive, many Denver ADU owners rent them short-term to help cover their loans, an anathema to long-term affordability.

When our governor Jared Polis began hinting at major land use reform to require ADUs statewide in late 2022, most of my peers in local government were opposed on the grounds of local control. I was intrigued.

I waited for the big case-making studies common before big legislation. I’d keep waiting until I decided to write that paper myself earlier this year. Before I did, not a lick of statewide data was available on what we in local government had already passed, who it was serving, the prospects we could expect from a statewide change. I had to dig for myself to learn the prices ADUs were renting for, and to whom, in other ADU reform communities or states. Regular Coloradans had access to no information at all beyond broad rallying cries that ADUs were “affordable housing.”

My full-length paper from May 2024.

Attempts to pass land use reform without showing communities how changes promote affordability, and without actual affordability components to serve even lower-income families, undermines the potential for widespread public support of those reforms. Less public support translated to less political support, first to pass ADU and other reforms at the state capitol (until lessons were learned and affordability funding was paired in a successful 2024 attempt). But more importantly, without broad support it’s harder sustain and implement ADU reform in the actual communities where they are built. I was awarded a Colorado Bell Policy Center Economic Mobility Fellowship to research the evidence and then to broaden understanding for when and how land use reforms like ADUs hold promise for greater affordability. The newspaper column below and this radio interview are examples of sharing the narrative with wider, public audiences.

I was a tough customer. But the evidence makes the case for the potential of ADUs: for some moderate income households on their own, and for more low- and moderate-income households with extra efforts and funding.

Denver Post Perspective Section cover of April 28, 2024.

Background on Colorado’s New ADU Legislation

Colorado’s first omnibus land use reform bill that included state-wide zoning reform for ADUs, SB23-213, crashed and burned at the close of our 2023 General Assembly. But legislative sponsors learned from their mistakes, and land use reform was reborn in 2024 with a package of separate bills. Most included funding for actual regulated affordability or menus requiring local governments to employ affordability strategies, or both.

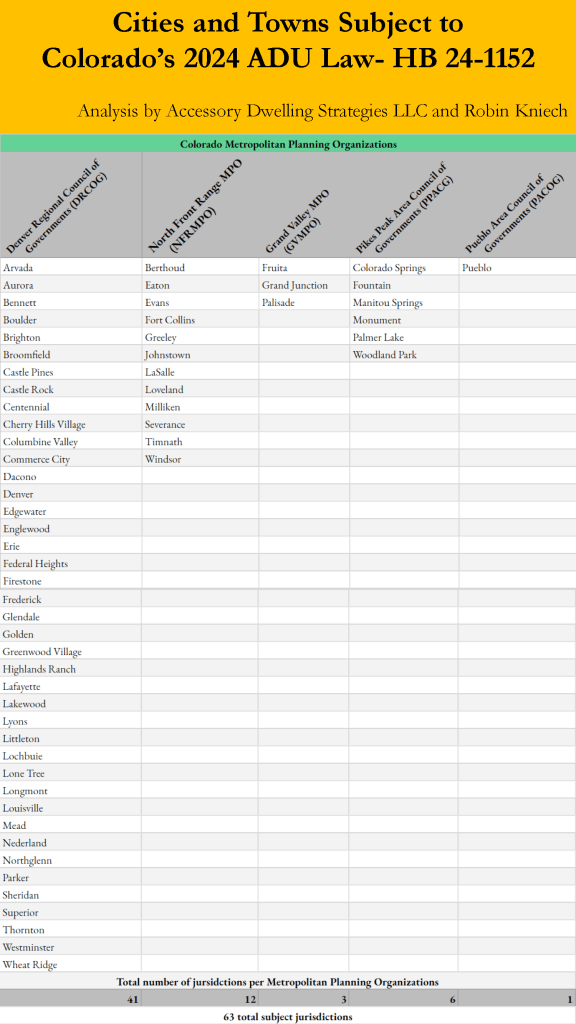

HB24-1152 was the 2024 bill dedicated to legalizing ADUs in Colorado’s urban areas. It covers about 64 local governments (within metropolitan planning areas) and represents 65 percent of the single-family homes in the state. It comes with a voluntary opt-in path for the remaining rural and resort communities, $8 million dedicated to local government fee reductions, toolkits etc. and $5 million for low- and moderate-income homeowner subsidies. It passed in the final days of the 2024 Colorado General Assembly, incorporating many of the best practices proven to increase ADU production elsewhere, but with a few tweaks to get it over the finish line:

- By-right zoning for units between 500-750 sq feet

- Setbacks can’t exceed those for the primary dwellings (or 5 feet in the back)

- Minimum lot sizes can’t exceed those for primary dwellings

- Allows requiring a single parking spot only where no on-street parking is available and an existing requirement was in place as of January 2024

- Owner occupancy can only be allowed at the time of permitting, a first-of-its-kind compromise intended for those who want to try to deter investor speculation while ensuring no owner will be stuck with a primary home/ADU they cannot rent if their circumstances or the economy changes after permitting or construction

Communities are required to conform with these requirements by June 30, 2025.

What Will Happen Next with ADUs in Colorado

Litigation

You know that part in the wedding where the officiant asks if anyone objects? Well, local objectors didn’t have a vote before Colorado’s ADU vows were sealed by their state counterparts. But there is almost certain to be a legal challenge to attempt to annul implementation before that June 30, 2025 deadline. Colorado Municipal League is likely to line up and support a couple of its municipal members as litigants. Colorado is known for strong home rule protections, and land use is historically a local domain (the State of Colorado doesn’t even have a planning office). The challenge will not be frivolous. But the Governor’s team has clearly been preparing for more than two years, so arguments to meet Colorado’s legal test for proving the state’s interest in uniformity, and on the negative impacts of zoning restrictions on residents outside a single community’s boundaries, are surely well-developed. Stay tuned. The remainder of this analysis assumes no injunction issues and that the law survives challenge.

Pre-Implementation Production Will Continue to Rise Due to Local Momentum

My paper, Can ADUs Deliver on the Promise of Affordability for Colorado? includes the first-ever baseline data on ADU permitting in the largest 32 of the 64ish local communities required to allow ADUs under the new law.

Across the 13 jurisdictions with broad ADU zoning and available permitting data, ADUs are being permitted at an average estimated rate of 0.6 per 1000 single family homes per year.

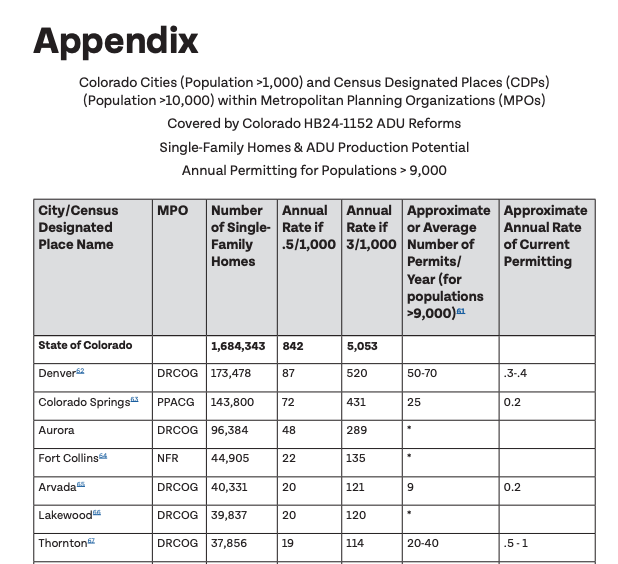

Excerpt of table of Colorado ADU zoning and permitting from my full length paper, which was created before the legislation was finalized. For a more accurate list of the jurisdictions covered under the final version of the bill, see the table at the bottom of this post.

Permitting was already on an upward trajectory in these cities even before the state bill passed. Several other cities had plans to take on ADU zoning at the time the state legislation passed. It takes many months to plan, finance, permit and then build an ADU. Therefore, any rise in permitting over the next 12 to 18 months will mostly be attributable to the local ordinances and efforts already in place or underway and not to the new requirements in the state law. Though increased awareness as a result of the state debate could boost homeowner interest.

Interest rates and inflationary pressures on construction pricing have made ADUs more expensive to build in the past several years. Until rates drop, they’ll continue to put downward pressure on the ADU potential that already exists, and perhaps even future potential if these economic forces persist after the state law is implemented. But Colorado’s on-going housing crisis has bred ADU momentum that seems to be outpacing inflationary cost pressures for families with means to pay the premium. At least at the permitting phase, as evidenced by activity over the past 24 months in the 13 jurisdictions I examined. Permitting and completing construction of an ADU are two different things, however.

Anecdotal evidence from the few communities with reliable data on completions indicates a rate of abandoned projects, or in cities like Denver where permits don’t expire, possibly extended delays. Twenty-seven percent of Denver ADU permits pulled since 2018 weren’t built or are still pending according to WDSF+. The program hears that surprise costs or escalation after permitting underly many of those stalled or abandoned ADUs. The state legislation did not take on what many argue are inequitable and overly burdensome infrastructure fees, for example (sewer connection, requiring pre-existing sidewalks to be brought up to code etc). With state legislation in the rear view mirror, homeowners and their ADU advocates will likely elevate concerns about cost and financing moving forward.

The state’s new $13 million in homeowner subsidies and local government grants will be an incentive for pro-ADU communities to come into compliance faster to access the money. A local government must meet the state standards and be designated as an “accessory dwelling unit supportive jurisdiction” to be eligible for local government grants or homeowner subsidies administered through the state. The jurisdictions most likely to see the quickest bumps in permitting under this scenario would be those whose zoning and regulatory systems need only minor adjustments.

If these local governments act quickly, and if the state is ready to actually certify them and disburse funds before the statutory deadline, it could provide a permitting boost or improve completion rates for the current and near-term pipeline of homeowners already working to design or finance ADUs–even before zoning implementation fully takes hold statewide and attracts a new generation of ADU aspirants.

Post-Implementation Production Will Rise Slowly in Communities New to ADUs, Faster in Those Making Only Tweaks to Existing ADU Laws

For the vast majority of jurisdictions that have no or overly restrictive ADU zoning today, implementation of the state guidelines is their first step, or hurdle. Some will relish the opening, helping them overcome vocal but perhaps not overwhelming opposition. Others will be opposed themselves, or face or fear backlash resulting in resistance. There are no explicit or unique penalties for missing the deadline written into the legislation, though the state has insisted it will have the legal power to compel compliance. My bets are on a slow and cautious approach to doing so. The ADU bill is only one of several land use reforms to pass this year, and the state will be reluctant to pick high profile battles before trying collaboration over long lead times.

Assuming a best-case scenario of using the next year to pass a conforming ordinance by the deadline, then a year or two to get the review and permitting systems running smoothly and to build interest among homeowners, who also need time to design and get financing: it will be 2+ years before many permits issue under first-time ordinances directly attributable to the state legislation. Expect 3-5 years to see many of those ADUs built and occupied.

Again, however, the effects of state reform should be felt more quickly as the causal factor increasing permit rates faster than they would have risen otherwise in cities already building ADUs. Conformance for these cities will mean dropping parking requirements for most (if they use use the narrow state exceptions) or all parcels, and removing long-term occupancy requirements. Both the largest city in the state, Denver, and the top ADU-producing community statewide, Boulder will have to undo long-term occupancy requirements and Boulder will also have to eliminate parking requirements. If changes take place by the one-year deadline in these and other cities already building ADUs, permits could begin rising immediately upon local ordinance passage/at the start of year two, as some homeowners will begin planning now and wait to take advantage of the new standards.

If Colorado were to achieve 3 ADUs per 1,000 single family homes throughout all the areas subject to the new state requirements (a baseline based on a recent average permitting rate across the state of California), it would represent 3,300 ADUs/year.

But How Will We know?

Missing from Colorado’s new law is a data collection or reporting provision, aside from those receiving grants, to ensure the public can efficiently monitor ADU production post-passage across all the covered jurisdictions. It was likely omitted to minimize burdens and soften opposition from local governments.

As I can attest, collecting this data city-by-city is a mean task. And as evidenced by the lack of third-party research before introduction and my own, Colorado lacks a home-grown, well-funded academic research center or think tank focused on affordability and/or land use likely to do so with any regularity (think the UC Berkeley Terner Center in California or the NYU Furman Center in New York).

If Colorado’s law survives challenge, I predict a future effort to amend the bill for more reporting. In my paper I comment that the marginal burden of reporting is nominal in comparison to the underlying zoning and regulatory reforms themselves, and it could be phased-in, starting with larger jurisdictions with more staff first.

What Will the People Say?

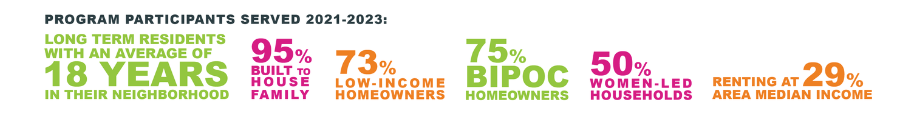

The ADU bill had one Republican co-sponsor but was opposed by most others in that party; its passage was made possible by a (not-quite unanimous, but close) Democratic trifecta controlling both chambers and the Governorship. Governor Jared Polis and legislative sponsors were well armed with favorable polling on a generic state-wide ADU requirement going into the 2024 session.

January 2024 poll by Keating Research from Centennial State Prosperity.

The Governor is not up for re-election and will be termed out in 2026. Because Colorado has turned overwhelmingly blue, only a handful of legislative seats will be seriously contested in the general election. Passage of this year’s historic package of land use bills alongside renter protections gives the majority a strong record to demonstrate action on housing affordability, but the races won’t be competitive enough to tell us what voters really think about ADU implementation at home in their local neighborhoods. Those of us who’ve been around the block understand that overwhelming poll support for high-level affordable housing solutions can erode quickly when change comes to residents’ blocks.

That said, regardless of whether legislators need case-making to win state races, proponents would be well-served by broad and sustained communication efforts to break down the explanation for why and how ADUs can expand affordability. This includes talking about the specific incomes likely to be served by market-rate homes and who is struggling in those brackets (my analysis points to 80% of AMI renters). And touting the paired funding already coming along with opportunities to identify more, to replicate models like WDSF+ to serve more low- and moderate-income homeowners in more communities across Colorado.

We also, all, need to talk a lot more about attached ADUs, aka basement conversions. They are cheaper to build and can blend into communities more easily than detached models, especially those with more suburban block forms, no alleys. And no one uses pictures of them or talks about them when broadly promoting ADUs. (Unfortunately, to maintain uniform and easily replicable pre-approved designs, the WDSF+ pilot doesn’t support attached ADUs).

In my 12 years in elected office I’ve seen 5 colleagues defeated in elections that turned on anti-growth/anti-development sentiments. Three of the communities now governed by this ADU legislation passed growth limits at the ballot box (now preempted under 2023 legislation). If state leaders expect ADU legislation to succeed, they need to follow zoning legislation with not just technical assistance, but communications and political support for local elected officials on the front lines. And funding will have to keep flowing to help low- and moderate-income Coloradans actually build them to meaningfully deliver on the promise of affordability.

Colorado’s ADU marriage can be a happy one, but like all relationships, it will take hard work that only begins once the honeymoon celebrating the passage of our first bill is over.

~

If you’d like to read more of my analysis of Colorado land use, affordable housing, other equity and political issues you can follow me at Robin Kniech’s New Take on Substack.

This blog post was revised at 7:11 pm on 7/10/24 to correct typos in the bill number, and to update the total number of jurisdictions and percentage of the state covered by the final version of Colorado’s ADU law HB24-1152 signed into law and to add the table of covered jurisdictions below.

You must be logged in to post a comment.