Accessory Dwellings

A one-stop source about accessory dwelling units, multigenerational homes, laneway houses, ADUs, granny flats, in-law units…

Dwelling in the Urban Alleys of DC

A book review of Alley Life in Washington

(Editor note: this is part one one of a two part series. You can read part II here.)

Alley Life in Washington is one of my favorite books. Not just because of the story it tells about the history of a hidden part of Washington DC, but because I believe it also suggests a way forward — in terms of compact, more affordable urban living – if DC residents were allowed to build in places where the city housed 20,000 people in its past.

In this impressive study, the author, Jame Borchert, traces the formation of occupied alleys populated mostly by African-Americans who migrated from rural areas to Washington, DC starting in the Civil War era. He argues that they created strategies to survive the often harsh and difficult urban experience by remaking the urban environment physically and cognitively to fit their physical, social and spiritual needs–essentially adapting their rural folk culture to the urban landscape.

He also challenges earlier studies that were used to justify outlawing alley dwellings and accessory dwelling units on DC’s occupied alleys.

On the eve of the Civil War, Washington had still been relatively small, with only 60,000 residents.The population of Washington City nearly doubled to 110,000 a decade later. Nearly half of the new migrants were black.

In many of the larger blocks that were distributed throughout the Federal City, developers responded to population growth by building on both a street and its alley—often nearly simultaneously. The assumption seemed to be that the middle classes would live on the streets, while working-class people would reside in the alleys.

The vast majority of residents living in these alley communities within the blocks were black. But unlike the segregated residential patterns that were to follow, the alleys and their residents were dispersed throughout the city, often in close proximity to the most expensive and elegant houses.This may help explain the description of the black community as “The Secret City,” which Constance McLaughlin Green called her 1967 account of race relations in Washington.

In the 1870’s Washington possessed neither sufficient buildings to house the newcomers or any efficient means of moving them daily from one part of the city to another. For those with enough money or leisure time, horse-drawn cars did offer the rudiments of a transportation system. But because most peoples journeys about the city remained pedestrian ones, there was a substantial impetus for the continuing and expanding alley dwelling construction, an intuitive strategy to provide more housing near the urban core of the city.

The boom in building permits in “inhabited Alleys” stopped in 1892, when Congress approved legislation that effectively stopped further building.The 1892 Legislation prohibited further housing construction on alleys less than thirty feet wide and not provided with sewers, water mains, and lights.

Reform-minded citizen groups began agitating for the abolition of alley housing around the turn of the century. Roosevelt urged Congress to conduct a systematic study of the alleys. The Board for Condemnation of Insanitary buildings, reported 375 houses destroyed and 315 repaired from 1906 to 1911. By 1914 the First Lady, Ellen Wilson, led “grand tours” of the alley with the Cream of Washington Society and actively sought passage of legislation to end alley dwelling. World War I and the accompanying housing shortages led to postponement, and the legislation that eventually went into effect was emasculated in 1927 by an adverse court ruling.

But where the reform movement failed to bring about much change, economic factors were transforming the land use of alleys. Warehouses, shops, and businesses replaced some houses. By 1928, automobiles had become a major factor, as a substantial number of former alley residences were converted into garages. The city trolley was also providing an inexpensive and efficient means of transportation, permitting population dispersal, and diminishing the pressure that helped create alley housing.

Carl Mydans: Outside water supply, Washington, D.C. Only source of water supply winter and summer for many houses in slum areas. In some places drainage is so poor that surplus water backs up in huge puddles. 1935.

By the time that Mydans was photographing Washington’s alleys and the people who lived in them – during the great depression – Washington’s “mini-ghettos” had been a matter of public concern for at least two generations prior to the great depression. Outsiders, especially middle- and upper-class outsiders, increasingly saw alleys as little more than incubators of crime and disease.

Congress, which had the final say in governing Washington, passed the Alley Dwelling Act, “to provide for the discontinuance of the use as dwellings of the buildings situated in alleys in the District of Columbia.” No alley houses were to be inhabited after July 1, 1944.

But as with the former reform movement, a world war and the resulting housing shortage postponed enforcement of the ban – this time until 1955.

Suburban tracts spread farther and farther from the city during the late 1940s and 1950s, while a small counter movement of citizen groups involved with the restoration of Georgetown, Foggy Bottom, and Capitol Hill was growing. In 1954 citizen’s groups involved in the restoration movement successfully engineered a repeal of the ban on alley dwellings that was to go into effect the following year. By 1970 at least 20 inhabited alleys remained with 192 heads of household reported in the city directory.

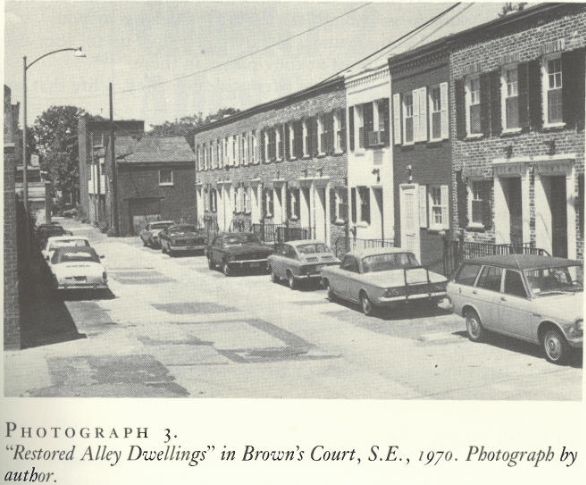

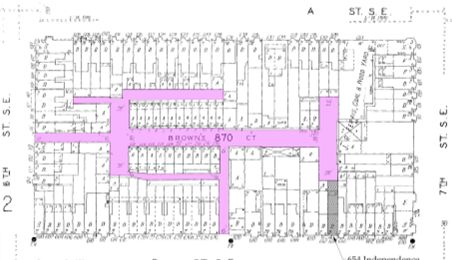

Browns Court is 6 blocks East of the Capitol Building. It includes a number of continually occupied alley dwellings that the restoration movement helped to save. Brown’s Court still has a mix of rowhouse alley dwellings that date back to the 1860’s, as well as one-story garages and two-story carriage houses, some of which have been converted for residential use.

But the historic alley dwellings are now hardly affordable housing. One of the 14’ by 24’ two bedroom, one bathroom homes is currently on the market now for over $500,000. Thus the alley dwellings which became “mini-ghettos” for black residents during the civil war are now expensive and highly sought-after residences for affluent Washingtonians.

A closer look at Browns Court shows the potential for Accessory Dwelling Units that could replace many of the existing garages – if owners were allowed to build ADU. My next post will deal with some expensive lessons I’ve learned about the path towards getting a permit for building an ADU in DC – and an invitation for someone who would like to build one on Brown’s Court.

I ran across another alley-dwelling article not too long ago. http://daily.sightline.org/2011/09/08/home-home-on-the-lane/

I’d love to see this development trend grow.

Another Article

http://wamu.org/programs/metro_connection/12/05/25/dcs_alley_dwellers_live_in_the_heart_of_it_all_out_of_sight

Pingback: The Many Chapters of Small Living | Intentionally Small

Pingback: Alleys: DC’s Other Streets Are Attracting Attention – Shilpi Paul

Pingback: Dwelling in the Urban Alleys of DC (Part II) | Accessory Dwellings